Are companies ready to face climate litigation? An analysis of global and national trends

The climate emergency and the many questions it raises to society are resulting in a growing litigiousness of environmental issues involving public actors and increasingly private actors.

This trend has been highlighted in the 6th report of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change which pointed out for the first time the importance of legal disputes in the reconfiguration of global climate governance.[1]

The notion of “climate litigation” has quickly become blatant to observers as a global judicial trend resulting in a strong mobilization of civil society. It encompasses all litigation brought before judicial bodies involving important environmental issues in the field of science, policy, or law.

Several academic teams around the world, such as the Grantham Research Institute, areinventorying and analyzing this type of cases.[2] They point to a trend of increasing climate litigation. The total number of climate change cases has doubled since 2015, from 800 to around 2,000 today. In France, two-thirds of pending climate cases have been filed since 2019.

Alerion has set up a legal observatory to draw lessons from French climate litigation and the international cases deemed most relevant.

This work makes it possible to analyze trends in climate litigation on a global scale and to compare them with French cases. The main issues will be presented on a regular basis.

Companies are increasingly targeted

Private actors are denounced as the main polluters, but until recently, states remained the preferred targets of plaintiffs (70% of litigation initiated in 2021).

The Urgenda decision in the Netherlands[3] is a landmark case in Europe. This decision rendered in 2019 had an international impact because it established for the first time the obligation for a state to comply with global greenhouse gas reduction targets, particularly in the framework of the Paris Agreement, whose main objective is to limit the increase in the average temperature of the planet “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels”.[4]

In France, this trend was followed by two major decisions of the administrative courts. In the Grande-Synthe case, the French State Council (Conseil d'Etat) imposed a climatic obligation on the French State and innovated by introducing the notion of “trajectory” (for the reduction of greenhouse gases), which it undertakes to control.[5] Thus, the French government was ordered to take the necessary measures to achieve the objective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, it being specified that it must submit to the Council of State a periodic report on the measures taken[6]. In the Affaire du Siècle case, the Paris Administrative Court (Tribunal administrative) took a major step forward by admitting the possibility to raise an environmental loss[7] against the French State. [8] In this case, the French State was ordered to take all necessary measures to repair, before December 31st, 2022, the environmental loss caused by exceeding carbon budgets in breach of its climate commitments.[9]

While most of these disputes are brought before national courts, lawsuits are also filed before supranational bodies targeting states’ failures to meet their commitments to combat global warming.[10] Recently a French deputy was heard by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), concerning the insufficiency of France's action in the fight against global warming[11]. Similarly, six young Portuguese people are arguing, before the ECHR, that 33 states (including France) have violated their right to life[12] and to a private and family life[13] by breaching their obligations under the Paris Agreement.[14] The Grand Chamber will have to answer first on the admissibility of the claim since the lawsuit was brought directly before the ECHR without complying with the procedural rule of exhaustion of domestic remedies. The claimants allege that fulfilling such a requirement in all the relevant states represents an excessive and disproportionate burden considering the climate emergency.

The concentration of lawsuits against states characterizes the first climate change legal battles but should not mask the rapid increase of lawsuits against companies. This trend can be observed both at a global level, with the number of lawsuits almost doubling between 2020 and 2021 (38 vs. 22), and at a national level, where approximately 70% of litigation against companies was filed after 2018.

Most of the sued companies are being sued by NGOs. In their pursuit of climate justice,Amis de la Terre, Greenpeace, and ClientEarth are suing private actors on all five continents. In France, all climate related cases against companies have been initiated by NGOs.

This new form of climate litigation is enabled by the development of new constraining legislation for companies. Between 2015 and 2022, more than 300 climate laws have been passed worldwide.[15]

France stands out with the law on the “duty of vigilance” (devoir de vigilance), which provides an instrument for taking legal action against groups having at least five thousand employees.[16] The main obligation imposed on the companies concerned is codified in Article L. 225-102-4 of the French Commercial Code which provides a duty to establish and implement a “vigilance plan” (plan de vigilance) against risks of serious human rights and environmental violations.

The actions target new sectors of activity

Originally, climate litigation against private actors was almost exclusively directed against “Carbon Majors”. This term encompasses the major fossil fuel producers (Shell, Exxon, Chevron...) responsible for two-thirds of industrial CO2 emissions.

In France, with the notable exception of the Casino[17] and Danone[18] cases, most of the litigation involves the liability of oil companies. The Total case is a good example: NGOs allege that, despite its vigilance plan, Total has not set out in detail the measures to be taken to actively reduce its contribution to climate change and comply with the Paris Agreement. The plaintiffs requested the interim relief judge of the Paris Judiciary Tribunal (Tribunal judiciaire) to order Total to comply with its obligations under the law. The judge ruled that these requests were inadmissible for lack of formal notice prior to the referral to the interim relief judge.[19] The interim relief judge also stressed the limits of his powers in the framework of the law on the duty of vigilance. Therefore, a decision on the merits is needed to have a better understanding of French courts’ control regarding the duty of vigilance.

French courts might be tempted to follow the precedent established in Milieudefensie v. Royal Dutch Shell casein which Dutch judges ordered Shell to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 45% at the latest by 2030.[20] The Dutch judges based this decision on the “duty of care”standard provided underArticle 6:162 of the Dutch Civil Code, which is comparable to the extra-contractual liability rule provided under Article 1240 (formerly 1382) of the French Civil Code.

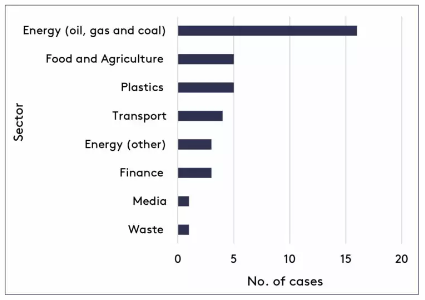

The spectrum of private sectors involved in climate litigation is growing. The Grantham Research Institute's chart, listing lawsuits against companies over the year 2021, illustrates this trend:[21]

Climate litigation, particularly initiated by NGOs, is increasingly involving stakeholders in the textile or agri-food industries.[22] At the beginning of 2023, the NGOs Zero Waste France, ClientEarth, and Surfrider Foundation Europe announced that they filed a suit against the French food giant Danone for failure to comply with its duty of vigilance[23].

Moreover, all companies should pay particular attention to their communication regarding their initiatives to deal with the climate emergency. From now on, they can be accused of “greenwashing”.[24] These lawsuits for misleading communications affect many sectors such as energy,[25] transport,[26] or finance.[27]

Toward the development of individual liability

Emerging trends in climate litigation appear to focus on individual liability ranging from criminal complaints to actions based on corporate officers’ duties.

Indeed, individuals choose to take legal action against companies for compensation for their environmental losses.

For example, in the case of Luciano Lliuya v. RWE AG, a Peruvian farmer filed a lawsuit against the German energy giant for contributing to global greenhouse gas emissions.[28] According to Mr. Lliuya, RWE AG is partly responsible for global warming which is causing a glacier to melt which risks flooding the city of Huaraz, Peru. If the German judge rules in favor of the Peruvian farmer, this would imply a very liberal rewriting of the causal link.

There are also lawsuits based on the duties of corporate officers regarding climate risk management.

The first case of such kind is ClientEarth v. Board of Directors of Shell, in which the NGO argues that Shell board of directors’ failure to adopt and implement a climate strategy that is truly consistent with the Paris Agreement is a breach of its obligations.[29] However, the High Court of England and Wales dismissed this claim, holding that prima facie the plaintiffs had not established that the directors had breached their duties[30]. This case will likely set an important precedent for targeted actions against corporate officers’ climate-related obligations.

In addition, similar legal actions could also be brought before the French courts based on Article L. 225-35 of the French Commercial Code, which requires boards of directors to determine the direction of the company's business “taking into account social and environmental issues”.

Criminalizing environmental losses is also a major international issue.

France has been a pioneer in this field with the “Climate and Resilience Law” (Loi Climat et Résilience) which incorporated the notion of “ecocide”into Articles L. 231-1 et seq. of the French Environmental Code.[31] Given the particularly rigorous conditions for the characterization of this new offense, its interpretation by courts will be followed with interest.[32]

Apart from its political aspect, the case involving former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro could establish a new link between environmental destruction and international criminal liability.[33] It will be up to the International Criminal Court to study whether the alleged damage caused to the Amazon by President Bolsonaro's administration can be qualified as crimes against humanity.

Conclusion

In the context of climate emergency, the increasing litigiousness of climate issues now represents a way of pressuring private actors to force them to seriously consider their impact on climate.

At COP27, UN experts called on states to regulate emissions from companies under their jurisdiction and to ensure that their courts can enforce such provisions.[34]

This call, which is in line with a strong mobilization of civil society, will lead to the multiplication and diversification of climate lawsuits against economic actors.

This evolution is accompanied by important changes in our legal culture, which could be confronted with a more liberal theory of liability or with the emergence of the legal personality of ecosystems.

In France, without a major decision on the merits involving a private actor, it is still early to predict future trends in climate litigation. Pending judgments will be scrutinized by Alerion with the utmost attention.

To go further:

C. Cournil, Les prémices de révolutions juridiques ? Récents contentieux climatiques européens, RFDA, September – October 2021, pp. 957 - 966

B. Lormeteau, Les contentieux climatiques en France : bref état des lieux, Lettre du réseau Eden, September 2022

M. Torre-Shaub, Justice climatique - Procès et actions, CNRS, 2020

C. Cournil et L. Varison (dir.), Les procès climatiques, entre le national et l'international, Pedone, 2018

C. Cournil (dir.), Les grandes Affaires Climatiques, Confluences des droits, Editions DICE, 2020

C. de Toledo, Le fleuve qui voulait écrire, Les Liens qui Libèrent, 2021

B. Latour, Où suis-je ?, Les Empêcheurs de Penser en Rond, 2021

C. Stone, Les arbres doivent-ils pouvoir plaider?, Le Passager Clandestin, 2018

S. C. Aykut, A. Dahan, Gouverner le Climat ?, SciencesPo Les Presses, 2015

Marta Torre-Schaub, Les contentieux climatiques, quelle efficacité en France ? Analyse des leviers et difficultés, Lexis360, May 2019

M. Torre-Schaub, B. Lormeteau, Aspects juridiques du changement climatique : de la justice climatique à l’urgence climatique, La Semaine Juridique Edition Générale, September 23rd, 2019 and December 23rd, 2019

Y. Aguila, Petite typologie des actions climatiques contre l’Etat, AJDA, 2019, p. 1853

[1] IPCC Working Group III, 6th assessment report, April 4th, 2022

[2] J. Setzer, C. Higham, Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation: 2022 Snapshot, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, June 2022

[3] Dutch Supreme Court, December 20th, 2019, 19/00135, Urgenda v. The Netherlands

[4] Paris Agreement, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, December 12th, 2015, entered into force on November 4th, 2016

[5] French State Council, November 19th, 2020, n° 427301, Commune de Grande-Synthe ; French State Council, July 1st, 2021, n° 427301, Commune de Grande-Synthe

[6] French State Council, May 10th, 2020, n° 427301, Commune de Grande-Synthe

[7] Environmental loss being recognized by civil and criminal courts since the Erika case (French Court of Cassation, Criminal Division, September 25th, 2012, n°10-82.938). Following this case, the concept of “environmental loss” was enshrined in the Civil Code in Articles 1246 to 1252. Article 1246 of the Civil Code provides that “[a]ny person responsible for ecological damage is required to compensate for it” and Article 1247 of the Civil Code defines ecological damage as “a non-negligible damage to the elements or functions of ecosystems or the collective benefits derived by man from the environment.”

[8] Until this case, Articles 1246 et seq. of the French Civil Code had not been recognized as enforceable against the French State by French administrative courts

[9] Paris Administrative Court, February 3rd, 2021, and October 14th, 2021, No. 1904967, Affaire du siècle v. France

[10] European Court of Human Rights, press release of 9 February 2023 on climate-related applications.

[11] European Court of Human Rights, n°7189/21, Carême v. France

[12] Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights

[13] Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights

[14] European Court of Human Rights, No. 39371/20, Cláudia Duarte Agostinho and others v. Portugal and 32 other States, application filed on September 7th, 2020

[15] Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, Climate Change Laws of the World - Laws and policies”, https://climate-laws.org/legislation_and_policies, consulted on January 19th, 2023

[16] French Law on the Corporate Duty of Vigilance, March 27th, 2017, No. 2017-399

[17] Saint-Etienne Judiciary Tribunal, summons against Casino on March 3rd, 2021, for deforestation and human rights violations in its supply chain, based on the French Law on the Corporate Duty of Vigilance

[18] Paris Judiciary Tribunal, summons against Danone on January 9th, 2023, for breach of the duty of vigilance regarding its deplastification objectives, based on the French Law on the Corporate Duty of Vigilance

[19] Paris Judiciary Tribunal, February 28th, 2023, n° 22/53942; Paris Judiciary Tribunal, February 28th, 2023, n° 22/53943

[20] The Hague Tribunal, May 26th, 2021, C/09/571932, Milieudefensie v. Royal Dutch Shell

[21] C. Higham, H. Kerry, Taking companies to court over climate change: who is being targeted?, LSE Business Review, May 3rd, 2022

[22] In September 2022, NGOs gave formal notice to nine food and retail giants in France to comply with their duty of vigilance under Article L. 225-102-4 of the Commercial Code

[23] Paris Judiciary Tribunal, summons against Danone on January 9th, 2023, for breach of the duty of vigilance regarding its deplastification objectives, based on the French law on the Corporate Duty of Vigilance

[24] French decree on carbon offsetting and carbon neutrality claims in advertising, April 13th, 2022, No. 2022-539

[25] For example: Paris Judiciary Tribunal, summons of March 2nd, 2022, Greenpeace France et al. c. TotalEnergies SE et TotalEenergies Electricité et Gaz France

[26] For example: Amsterdam Court, summons of July 6th, 2022, FossielVrij NL v. KLM

[27] For example: Ad Standards (Australia), complaint of September 16th, 2021, Ava Shearer v. HSBC

[28] Hamm Court of Appeal, summons of November 24th, 2015, Luciano Lliuya v. RWE AG

[29] High Court of England and Wales, application of March 15th, 2022, ClientEarth v. Board of Directors of Shell

[30] High Court of England and Wales, May 12th, 2022, ClientEarth v. Board of Directors of Shell

[31] French law on combating climate change and strengthening resilience to its effects, August 22nd, 2021, No. 2021-1104

[32] C. Lepage, Le délit d'écocide: une “avancée” qui ne répond que très partiellement au droit européen, Dalloz Actualité, February 17th, 2021

[33] International Criminal Court, complaint of October 12th, 2021, AllRise vs. Bolsonaro and others

[34] I. Fry et al., COP27: Urgent need to respect human rights in all climate change action, November 4th, 2022